- Home

- Monica Wesolowska

Holding Silvan Page 4

Holding Silvan Read online

Page 4

I sat on the toilet and thought about Maurice. I wanted my eyes to get, if not full of tears, at least wet. If I could cry a little, it would mean I’d been touched by death; I wanted to be able to go to school the next day changed by the knowledge of someone’s absence from the world.

But I couldn’t cry. Grief, it seemed, could not be practiced.

And yet, in some ways, I had practiced. I had understood that part of what makes absence acceptable is the life story that precedes it, the life story that remains. As I stood at Chmum’s deathbed years later, I tried to tell her I was pregnant. By now, my mother knew; by now, I had told David he’d better hurry up and adjust. “Are you still pregnant?” he’d ask each time I called and I’d say, “Yes,” impatiently; for with the deaths of my father, my brother, and soon of my grandmother, this coming baby seemed all the more necessary. I tried to tell Chmum in English. I tried in French. Finally, Chmum revived from her morphine haze, turned from the TV, grasped my hand in her hard, dry grip and said, “Ya ha! Ya ha!” – a cheer from my mother’s childhood – and then something else about the dance of life.

Chmum slipped away in her sleep a few nights later, taking most of Maurice and Dédé and the rest of her dead with her, and six months after that found me driving through Berkeley with my pregnant belly swelling against the steering wheel. How right everything suddenly seemed. For the first time since the deaths in my life, I felt truly optimistic and safe. In front of me, an old woman with unruly gray hair and an armful of flapping flyers stepped into the crosswalk. I slowed and came to a stop. Thin and wrinkled and dressed in faded blue sweatpants and a bright t-shirt from Guatemala, this old woman looked just like my mother. In fact, she was my mother. I beeped the horn. My mother turned. Her face broke into a bright smile. There was something different about her. She was fully an old woman now and also younger than she’d been before her mother’s death; in fact, she looked younger than she had in years. That was it. Her step was bright, her cheeks had color to them, she was smiling and waving. No longer the grieving mother, wife, and daughter, she was dancing to another tune, the tune of the expectant grandmother.

Chasm

WE TELL DR. A THAT WE NEED ANOTHER MEETING WITH him, just with him – no specialists, no residents, no social workers. It seems with him alone we can build some kind of bridge over this chasm the neurologist has opened beneath us. If Silvan will only have stiff limbs and poor grades, we would not feel suspended in quite this way. We already love him. We love him as a newborn – his loamy-scented head, the soft heft of his thighs, the tiny thump of the heart in his chest – and we love the dark-haired man with the cleft chin whom we are still in the habit of imagining he will become. But is his prognosis even compatible with future life? The neurologist has also said he may be deaf, blind, unable to move or swallow or even breathe on his own. Not only that, he’s currently in a coma. He’s no longer living on his own. By now, he has a fat tube down his throat to pump in air; an IV through his belly button to feed him. How long can he remain like this? How long can his life be artificially sustained?

This time Dr. A takes us to a smaller room, with a table and three chairs around it, surrounded by shelves of books. He is incredibly reasonable, patient with us. The whole time he is with us, we feel as if we are the only parents with a baby in the hospital. “This almost never happens, a baby with good prenatal care who goes through an ordinary labor,” Dr. A says. He repeats what we already know: no evidence of asphyxiation on the monitor tracings, a placenta that looked fine, cord-blood gases not much below normal. These are things I am learning about. I have learned that when a baby is in distress he defecates, and that his defecation is called meconium, and that meconium is dangerous if he inhales it. I know the meconium had alerted the doctors to Silvan’s distress, the meconium and his subsequent lethargy, the lethargy that had scared David so much while I lay there in my post-partum haze. But even Silvan’s Apgar score – that first evaluation of a newborn’s health – was not so low as that. “It still happens, more than we’d like, but less often than it used to,” Dr. A concedes.

Perhaps this is said to comfort us. Or perhaps Dr. A is simply airing his own discomfort at not knowing what happened. Worldwide, I will later learn, there are four to nine million cases of birth asphyxia each year. While most babies survive it, over a million die; over a million suffer severe disability. Many of these cases are due to poverty and poor health care, but still there remain the cases that are inexplicable. In the United States, asphyxia remains the tenth leading cause of neonatal death. Many of these cases are the inexplicable kind.

Not having an explanation may be hard, but what is worse now is my suspicion of the evidence. “How can he be this damaged,” I say, “when he seemed normal at birth? They took him for a few minutes, then said he was fine. Just lethargic. He even nursed.” And when he nursed, I’d obeyed the nurses. I had only let him nurse a few minutes on each side, not knowing this would be the only time, not knowing he would never cry to nurse again. Perhaps I should never have stopped.

Dr. A explains. When Silvan was deprived of oxygen, the cells in his brain began to die. At first, this damage was invisible. But after cells die, they swell, and these cells are now pressing on other parts of his brain, sinking him into his coma. Because a newborn operates mostly on brain stem, and because Silvan’s is still intact, he behaved before the coma, aside from the constant crying, like any newborn. His nursing was a reflex.

With time, the swelling may go down, and he may return to that instinctive state. But he will still be operating only on a brain stem; he will be unable to make more than basic movements; he will never develop mentally beyond this primitive state. “If he is lucky,” Dr. A explains, “he will be able to suck but not much more than that.”

“But what about the neurologist yesterday? She gave us a range.”

“You have to understand,” Dr. A goes on in his direct and honest way, “that no prognosis is certain. Sometimes with asphyxia, there is hope. With mild cases, some children recover entirely. Or they develop mild learning and behavioral problems. But with the burst suppression pattern that we saw on the EEG …” He tells us he stayed up much of the night researching cases of this exact pattern. “It’s extremely grim,” he says, shaking his head. “Extremely grim.” He tries to describe the life of a child with little but a brain stem. A life of living in a hospital bed hooked up to machines. I picture a newborn in the curled-up body of an adult. I remind myself that he may not see or hear or speak or eat or move, but none of these are certain. Dr. A says he could order another test, but he suspects that this test will only confirm the grimness of the prognosis, since Silvan has already had a CAT scan and three EEGs. He wants us to know that there is a waiting list for this extra test, that it is expensive, that it would make our baby uncomfortable. He wants us to know that, despite all this, he is willing to pull rank, to insist that we go to the top of the list and have this test immediately if we need more confirmation.

With this offer, we have to make our first, concrete moral choice. Should we have another test that will make our baby uncomfortable just to make ourselves more comfortable with a prognosis that is already as certain as a prognosis can be? Should we “pull rank” over others who need this test? Should our baby receive “heroic” attention when others are dying in unnecessary, neglected misery?

I have a bag of nuts. I am ravenous post-partum. I keep the bag of nuts open between us because I must eat to keep up my strength for these conversations in which so much must be heard and acted on. My appetite is endless. I offer Dr. A some nuts. He takes one politely, allowing me to mother him because he is compassionate and maybe understands that the need to mother someone is raging in me.

“So the range was to give us hope?” David asks.

“A prognosis is never certain.”

“We understand that,” David says. “But if the prognosis is as grim as it sounds, we need to know what this means for his life.”

Dr. A begins with telling us that Silvan may never revive from the coma, or he may die of a seizure. Or, if he does revive and try to nurse, lack of coordination will cause him to inhale milk each time. This inhalation of food will give him recurrent pneumonia. He will have to return to the hospital over and over to be saved. He will most likely die before reaching the age of one, but he may go on longer than that.

“What would have happened if he hadn’t been given oxygen at birth?” I suddenly ask. After all, this was why they had wheeled him away, to revive him. And right before this meeting, a nurse let slip that Silvan had started turning blue again that very morning. This is why he is now on a breathing tube. “You should have seen us running around to save him,” she said. I am starting to understand that already many choices have been made about his life without my knowledge.

“That’s hard to know for sure,” Dr. A says, “but unlike adults who struggle to breathe, babies react to a deficit of oxygen by breathing less and less until they stop breathing altogether. He may have just slipped away.”

“How frustrating,” I say.

“How so?”

“To think that we are in this situation because he was saved.”

“We couldn’t let him die at birth,” Dr. A says. “Not before we knew what was wrong with him.”

“Of course not,” I say, but still I am frustrated. He has been stopped from dying in the most peaceful way possible. He’s been thwarted in the only act he’s tried to take.

“But what if we think it’s wrong now to keep saving him?” David asks.

“Some parents don’t treat the pneumonia. They allow their children to die that way.”

“And some parents let them die of seizures?” I ask.

“It happens sometimes.”

“How awful,” I say. “Is there no other way to let him die?”

And so, he tells us. He tells us that in the case of a newborn with a prognosis as grim as Silvan’s, coupled with a coma and inability to take nourishment orally, it is legal to withdraw all food and liquid. I have no memory of this moment, the shock of learning this truth that, though euthanasia is illegal, you can starve a person to death. I do not remember the sound of Dr. A’s voice, nor his actual words. What I remember instead is that one moment I am in despair for Silvan, and the next I have hope.

CEASING TO EAT used to be the most common precursor to death, prior to feeding tubes and other interventions, prior to medical situations such as ours. Most deaths prior to the twentieth century were preceded by a few weeks of illness, then a few days of not eating. People used to recognize the approach of death this way, the body’s natural way of letting go. Instead of being painful, it seems that giving up food has a palliative effect. This effect doesn’t happen for people who are trying not to starve, children who are getting tiny amounts of food or liquid, for example. But within twenty-four hours of giving up all nourishment, our bodies enter a state in which appetite is suppressed, pain diminishes and we feel euphoric. This is what happens when people fast. We can’t know for sure, but this seems also to be the case for people who are dying.

This is what Dr. A tells us, after we ask. For of course I don’t want Silvan to suffer more in dying than he would in living. I need to know what he is in for. However, Dr. A warns us, “Newborns are born with great reserves of fat. With a healthy newborn, this can take a long time.”

“How long?” David asks.

Dr. A doesn’t know for sure. “It could be weeks. If you decide to go this route, we’ll make sure he’s comfortable of course. We’ll have morphine, and also lube for his eyes and lips if they get dry.”

As if to test Dr. A’s confidence, David asks, “What would you do in this situation if it were your child?” But Dr. A only smiles sadly, shakes his head. “You are the parents. You have to decide. I know it’s hard…” And then, “I was once in a situation like this, almost in a situation like this, with my wife.” Though Dr. A has not told us how he himself would act, it is comforting to know that he has at least imagined himself in our situation, that it is possible to imagine such a death.

Dr. A wants us to go home and think about our decision before taking any action, but how strangely certain I feel. If Silvan should be spared his life, there seems no justification for stalling. I feel as if I have been studying for this moment my whole life. Now is when I will pass or fail. I can’t ask Silvan what he would want for himself, so I have to rely on what I would want for myself, what I believe about life and death, what makes it good or bad. For now, this knowledge is purely instinctual. If I love him, I will let him go.

Dr. A looks exhausted from being doctor to a child he cannot cure but remains patient and present. He declines eating more of my nuts but does not stir from his chair.

“Are you sure?” he asks over and over.

Silvan may die at any time but he might not and we need a plan, a plan to make up for the fact that his life has been artificially saved until now. We will start by removing the phenobarbital, we decide. “Without the phenobarbital, Silvan may wake up. Or he may have a seizure and die,” Dr. A warns us and waits to see how we react. We nod. “If he doesn’t die of a seizure, we can remove his breathing tube. Again, he may die; or he may not.” Again, we nod. “If he keeps breathing, we can remove the intravenous food.” At each step, we nod.

“Are you sure?” he repeats.

Suddenly I have a question. “Will the nurses…” I say. Just as suddenly, my voice breaks. Dr. A looks alarmed. Have I become unsure after all these hours? “Will the nurses be kind… to a baby…who is dying?”

Panforte

PERHAPS CRISIS ALWAYS BRINGS US BACK TO CHILDHOOD, but I seem to be reverting. As we prepare to leave the hospital that night – Dr. A still wants us to go home and think about our decision before taking any action – we run into an acquaintance. She works on a different floor but has heard about Silvan through mutual friends. She has been looking for us to tell me what she tells very few people – she had a stillbirth before she went on to have the rest of her children. She is very beautiful, with smooth, olive skin and green eyes that mock the dull green of her scrubs. Her living children, whom I have met at a party, are just as beautiful. Standing too close to me, her earnest eyes on my face, she says, “I want you to know that whatever happens, you are strong enough to survive this.”

And I resist her comfort. “You were probably younger than me when you lost your first,” I say, as if my suffering needs to be greater than hers, as if this is a competition I need to win to make what I am losing acceptable, as if by proving that I am the champion of pain, I will be rewarded enough to make this pain worthwhile.

“But I had fertility issues,” this well-meaning friend of a friend says, opening her green eyes wider, playing along. We take a step away from each other, squaring off like fighters.

“Of course,” I say, catching myself, “you’re right. Thank you.”

IT ISN’T FAIR, I think bitterly on the way home in the car; and then I remember my father trying to teach me not to think this way. “Nothing’s fair in life,” was his constant refrain, his greatest moral teaching, used mostly to head off petty arguments. Thursday evenings in my childhood, my father always had to “hold down the fort” as he put it, while my mother had choir practice down at the church. One Thursday evening in particular, my perfumed mother came wafting through the dining room, kissing us all goodnight, leaving my father in charge of a special dessert. There it sat, a panforte smaller than a Frisbee and many times heavier, all blackened fruit and nuts, on a plate beside him. I couldn’t believe our luck – panforte on this ordinary Thursday night – it felt like Christmas. He began the task of cutting and distributing as equally as he could to four kids. He passed the first piece to me. Then I watched him cut the next. It was a good-looking piece, too, and as I would relate it to myself later, I thought, I will be polite and pass this down to Katya.

Abruptly, my father changed the position of his knife. “For holding out for a bigger

piece than your sister,” he said, “you get half.”

I howled at the injustice. I told him I was being polite, generous, self-sacrificing. When he didn’t believe me, I stormed from the room to hide beneath my green desk, pulling the desk chair in after me. From the comfort of my little green cage, I told myself I was right. By refusing to come out, I was punishing my father. When he saw the unfairness of my suffering, my father would give me the respect I deserved. But the longer I sat, the more complex things became. Even as I stewed in righteous pride, I felt as if my father could see a deeper truth. He could read between the lines of my own story. For the truth was, had that next piece not looked equal to the one in front of me, I would not have passed mine down whereas my father wanted me to accept that, even if the next piece was smaller, my life was fine. He wanted me to be grateful for whatever I got – and I refused. For being good, for caring about others, for suffering enough myself on behalf of those others, I thought I deserved at least the same as everybody else.

“IT’S NOT FAIR,” I say to David anyway when we get home that night. The certainty of our beautiful green-eyed acquaintance that I will survive has not comforted me, coming from someone who has reached the other side. A stillbirth is easier, I think cruelly; she went on to have more children; she has no idea what I am suffering. Instead of letting myself be crushed by what we’re enduring, I swell with arrogance over it.

But David is like my father. He won’t brook melodrama. “If anything,” he says, “we’re lucky Silvan’s prognosis is as bad as it is.” And that’s true. Although Dr. A has said David and I need to discuss this further, we barely need words to come to agreement. Because Silvan’s prognosis is as bad as it is, because something much worse than stiff limbs and poor grades are in his future, we aren’t faced with as much of a moral quandary, as much of a threat to our marriage. Silvan is in a coma. He’s being kept alive artificially. Even if he revives, he’ll never be able to survive on his own. Even if he revives, it will be to a life of constant dying. We sit on the couch together holding hands and feeling certain. We are still in shock; in some part of ourselves, we must still believe the baby we’re waiting for has not yet arrived. But at the same time, we’re certain this very same baby has arrived and is ready now to leave. We need such certainty to act.

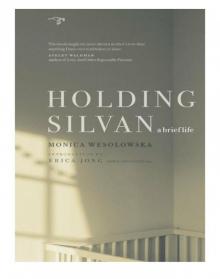

Holding Silvan

Holding Silvan