- Home

- Monica Wesolowska

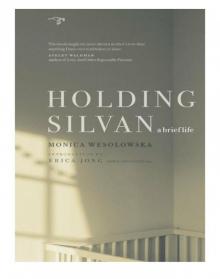

Holding Silvan

Holding Silvan Read online

Table of Contents

Praise

Dedication

Title Page

Introduction

Epigraph

Birth

Love Story

Making This Easier

I Hope Mommy Dies

Chasm

Panforte

A Choice

Confirmation

Distillation

We Climb

From A to Z

Battles

Chance of Regret

Holding Silvan

Breaking Plates

Seed Pearls

The Future

Goodbye, Little Man

First Night

Circuit Tester

Miracle Baby

Joy

Full Circles

Fledglings

Mutation

Crows

Sunshine

Acknowledgments

Copyright Page

Praise for Holding Silvan: A Brief Life

THIS BOOK CLEARLY deals with a dark, difficult, and important subject. I can’t imagine anyone better equipped to do full justice to such a profound human experience.

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM, author of By Nightfall and The Hours

I WAS SWEPT AWAY by this book. Heartfelt, heartbreaking and brave, it takes us on a fascinating ethical journey in prose that shines with Wesolowska’s love for her son. I feel fortunate for the experience, as if I have held Silvan myself. I’ll never forget it.

JULIA SCHEERES, author of Jesus Land and A Thousand Lives

A TENDER, POIGNANT and courageous narrative – insightful and beautifully written.

ABRAHAM VERGHESE, author of Cutting for Stone

WHEN I PICKED UP this book for the first time, my heart sank. I wondered if I could even bear to read such a sad story. And yet, within moments, I couldn’t put it down. I read long into the night, unable to leave the story until I reached its at once achingly tragic and profoundly life affirming end. That the story of the death of a child is, in fact, life affirming is a tribute to Monica Wesolowska’s graceful prose, her unflinching eye, and most of all her indomitable spirit. This book taught me more about a mother’s love than anything I have ever read before or since.

AYELET WALDMAN, author of Bad Mother: A Chronicle of Maternal Crimes, Minor Calamities, and Occasional Moments of Grace

WHEN SOMEONE WRITES about grief they also write about courage, since they survived to tell the story. The beauty and emotional integrity of Holding Silvan strikes me to the core. This book is brilliant.

LIDIA YUKNAVITCH, author of The Chronology of Water

For Silvan

Introduction

Erica Jong

THERE SEEMS NO MORE LIFE-CHANGING EVENT THAN having a child. But having a child who is destined to die must be more life changing still. How do we let go? How do we mourn? These are questions people have asked themselves since time began. The internet abounds with forums about infant loss but there are few honest memoirs chronicling that loss. When I looked for poems about this tragic event, I found mostly greeting card treacle. Is this one of those human events too deep for words, too painful to see purely?

Considering how common stillbirth, miscarriage and giving birth to damaged children are, it’s strange there is not more literature about it. In fact, current data tells us that 10-25 percent of all clinically recognized pregnancies end in miscarriage – no small number. And yet this experience remains largely unchronicled. Like the sun, it seems that death cannot be looked at clearly. It is too blinding, too fierce.

For centuries more babies died than lived. And mothers died giving birth. That is a part of our history we seem to want to deny. We want to forget all the mothers of past centuries who dreamed of nursing their infants to life and failed. That used to be an ordinary story. The fact that it is now extraordinary is only due to the recent triumphs of maternal and neonatal medicine. Some scholars have hypothesized that Frankenstein by Mary Shelley is a dream of reanimation invented by an author whose mother died a few days after her birth and many of whose infants died. Mary Shelley said the idea for the book came to her in a dream. The passionate pursuit of defeating death through science became the most enduring myth given us by a woman author. The Frankenstein myth undergoes endless permutations yet will not die. It shows us how deep our wish for denying death can be.

Holding Silvan is a memoir that takes us through all the stages of giving birth: hope, exultation, triumph. Then it becomes a meditation on loss. It is a book that takes us day by day, step by step, breath by breath through the process of letting go.

It teaches us the geography of mourning. It is an unsparing almanac of grief.

Monica Wesolowska discovers how hard it is for her friends and family to even utter the verb “die”. She takes us back to her childhood fear of losing her mother and how she tempted fate and tried to fool her dread by uttering the thing that she feared most. Sometimes we have to grab our fears by the scruff of the neck and tug. Only then can we domesticate our fears – like a cat.

We have never needed this book more. It comes as a rejoinder to all the superficial celebrations of childbirth that leave out its history and deny its meaning. How do you let go of a child you hoped to welcome day-by-day, breath-by-breath? Wesolowska tells that terrible story with utter simplicity and courage. It reminded me of the story of a mother dolphin carrying her dead calf on her back until finally she was ready to let it go. Giving birth brings out all our deepest mammalian feelings: the need to nurture, to protect, to heal – even when we have given up hope.

The hardest part of this book – for both author and reader – is Silvan’s lingering, neither wholly alive nor wholly dead. I marveled at Wesolowska’s endurance. I marveled at her transparent prose that was backlit with the deepest emotions, starting with love. This is truly the hardest kind of writing, and the most rewarding to any reader. It must have been excruciating to endure this passage and more excruciating still to memorialize it in words. All writers know that writing is not always catharsis. A door has been opened not closed. I hope Holding Silvan will inspire other writers to tell the truth about this passage.

I have always believed that children drag us into adulthood. Here, indeed, is further proof.

HOLDING SILVAN: a brief life

Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out.

VÁCLAV HAVEL

You’ll never know, dear,

How much I love you.

Please don’t take my Silvan away.

VARIATION ON “YOU ARE MY SUNSHINE”

Birth

IN THE MORNING, THE PHONE NEXT TO MY HOSPITAL bed rings. Stepping from the shower, my skin scrubbed of the sweat and blood of yesterday’s triumphant labor, I slip past David to pull on my old robe and head for the phone. I’m not worried. I’m expecting another friend, a relative, more words of congratulation to match my sudden pleasure in my baby – a healthy, full-term boy who waits for me in the nursery – but the woman on the other end of the line is a stranger.

“Hello, darling,” the stranger says in a husky, soothing voice. She is calling from another hospital. She says she needs to clear up some confusion about the spelling of my name before the transfer. I, too, am confused. When I tell the stranger that I don’t understand, that I am about to go down the hall to collect my baby because it’s time to nurse, she says, “I’m so sorry to be the one to tell you, darling.”

With these vague but tender words, the ecstatic glow of motherhood that has surrounded me since Silvan’s birth begins to fade.

An ambulance waits; the transfer is happening any minute. Wrapped still in my dirty robe wit

h its stiff patch of dried blood in back, I open the bathroom door and try to convey the stranger’s words to David hidden in the steam. Though David has told me his worries about Silvan since the birth, I’ve dismissed them all as mere symptoms of new fatherhood.

“Wait for me,” he says turning off the water, but there is no way.

If I could, I would fly to my son.

IN THE NURSERY, five people stand around Silvan’s bed. Five people. This is the baby’s “transport team” as someone puts it – two people to wheel the bed, one to drive, two more “just in case.” In case of what? In the night, when the resident had taken Silvan from me because he would not stop crying – mewls like a kitten, peeps like a bird – she only wanted me to sleep. She’d promised to bring him back when it was time to nurse. Even when she returned a few hours later to tell me they needed to keep Silvan for “observation,” I hadn’t begun to worry. I was too tired, too happy. I’d roused myself to go down to the nursery to see what they were worried about – cute little fist curls they called seizures. I’d held Silvan until I thought I’d pass out, then returned to bed without him. Nine months of hope is a hard habit to break. Besides, even if they were right in the night, he is totally calm now, sleeping peacefully. At last, he has stopped crying. Surely this is a good sign?

“It’s the phenobarbital,” they say.

I would stay beside his bed until they’ve wheeled him off to the ambulance, but a nurse comes in. She’s been searching for me, racing around coordinating my discharge. She needs me back in my room for an exam by a midwife. There’s paperwork to do, a birth certificate to apply for, milk to pump. She’s helpful but unpleasant. “Do you want to be discharged now or not? Because I have all my ducks in a row.”

Back in our room, my mother has arrived; David’s father and stepmother, too. I call out to them how cute the baby is – “just like David” – as they are ushered into the hall. The midwife spreads my legs. The breast pump arrives and I insert one breast into each cup, sign a birth certificate, agree to a home visit from a nurse and who knows what else, while the breast pump makes its thump and suck. Hospital staff tells me not to be embarrassed, they’ve seen it all before. David is searching the room for our possessions, which he stuffs into clear plastic bags provided by the hospital. The only thing he can’t find is the charger for his cellphone. It seems a small detail, too small to mention, but the symbolism is clear: soon we will become almost impossible to reach.

“HELLO MOM. HELLO Dad.” Shelley, the husky-voiced receptionist who’d called earlier, welcomes us to her hospital.

I am slow-moving but not in pain. Back at the other hospital, the last thing I’d done was put on my shoes and my mother had praised me for being able to stand on one foot so soon after birth – as if she herself is not equipped with such maternal strength. But maybe the recovery of my body matters as much to her as it does to me: it seems that this is the least I deserve, a body that can recover swiftly enough to care for a baby who must have been damaged while inside of me. For even though everything about my pregnancy and labor and delivery had seemed blessed, something has obviously gone wrong.

Shelley comes around her desk to hug us.

We are entering her world, the world of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, the dreaded NICU, a world where parents must dress in hospital scrubs to hold their children. Shelley shows us the routine: remove watch and jewelry, push sleeves above elbow, remove sponge and nail-pick from its plastic package, turn on water by whacking the metal knee pedal, get soap by depressing the squishy foot pedal, scrub, scrub, scrub thirty seconds each side, all the way up to the elbow.

On the whiteboard behind Shelley’s desk, I’m shocked to see my last name listed, proof that parenthood is not going the way I had imagined. Baby Boy Wesolowska, the whiteboard says, though our son’s name is Silvan Jerome Fisher.

DR. A IS a strapping man, almost-handsome, with steady, almost-kind eyes. Almost, I say, because he is not my baby and my baby is everything in the world right now. Anything else can only be almost. Dr. A speaks to us clearly and intelligently as Silvan’s neonatologist. We stand by the side of Silvan’s bassinet. Unlike many of the babies in bassinets around him, Silvan is plump and whole. Still he looks odd, lying by himself under a heat lamp.

Dr. A speaks with optimism but with an honesty that admits the unknown. His first diagnosis is best-case. “We have no evidence so far of anything but what we call subdural hematoma, a blood clot under the skull.” He says this happens sometimes during labor. After all, he reminds me that I pushed for several hours to get the baby around my pubic bone. Pushing for several hours is not uncommon with a first baby, but it’s not ideal. He holds up his hands to show us the plates of a baby’s head, and how they are still mobile, moving like continents. They are supposed to be this way, but sometimes when they crunch together in the birth canal they cause bleeding which leaves clots. These clots will shrink with time.

“This may cause seizures for him later in life, or it may not.”

With motherly pride, I assume it will not. And if it does, well, people live with seizures. My father, after whom Silvan has taken his middle name Jerome, had two seizures in his twenties. Though the seizures alarmed and embarrassed him, he went on to marry, have four children and a significant career.

And yet, as I hear the news, I feel faint. I say, “I have to sit.” And then I add, “It’s not because of what you’re saying.” Already, I know it’s important for this man to know that he can speak to me straight, that I don’t need to be coddled. I like honesty. But I do feel sick, woozy, and nauseated. Perhaps it’s a postpartum hot flash. “I just gave birth,” I remind him, apologetic, as someone wheels a stool my way.

THE NURSES TAKE over for a while. One brings me a little square of flannel. “Tuck this inside your bra or somewhere close to your skin and wear it for a day, then bring it back. We’ll put it by your baby’s nose so he can smell you while you’re not here. That will comfort him.” Another brings me bottles and shows me a room where I can pump milk.

“I know he can’t nurse right now, but when he’s better, we’ll start with the first bottles and go on from there so he doesn’t miss anything. That will also keep your own milk supply up and ready for him.”

I am stunned by their solicitude. Prior to his birth, friends promoted home births to me. Hospitals, they told me, were sterile, stressful places that ignored the wisdom of a mother’s body. At home, they seemed to think, nothing ever went wrong. But I liked my obstetrician, trusted her to trust me to give birth naturally. And I’d succeeded. For sixteen hours, I’d imagined ocean waves arriving and receding, getting high on my own endorphins as my body moved through novel pain, and then I’d pushed the baby out … but instead of being alert and drug-free, he’d been limp and silent. The triumph of that natural labor is now separating from the outcome as if the two events are unrelated. If this happened to him in a hospital, I tell myself, it could have happened anywhere. At least I’m not facing the blame for having risked a home birth; at least they’re treating me well, as if I am necessary and important, as if I am his mother. Because I am his mother, even if he is not in my arms.

WE RENT A breast pump to take home. That first night without him, I wake myself every few hours as if I have a newborn waking me, and sit in the dark living room, open my robe and put the suction cups on; the industrial-strength whirr and thump begins, the milk flows, my womb cramps as it’s supposed to do in the early days of nursing, and I cry. My sobs mingle with the whirr and thump until David distinguishes the human from the machine and leaps from bed to wrap his arms around me.

Over and over David leaps from whatever he is doing, sleeping, eating, talking on the phone, to comfort me, in the shower, over breakfast, in the car. He stops what he’s doing and focuses on me. He’s the one who returns phone calls, tells neighbors the news while I huddle over nothing in the car. He finds us gowns to put on at the hospital, gets us glasses of water to drink at Silvan’s bedside. He tends

to me so I can tend to our son. He’s always been good at tending to me. Ever since we met, I’ve known I could rely on him. This time, he hasn’t stopped moving since my water broke and he rushed around the house, putting dishes in the sink, packing my toothbrush, timing my contractions until – minutes later, it seemed, though David says it was an hour – it was time, I put on my old brown corduroy coat that strained at its buttons, and we went off to the hospital together.

EXCEPT TO SLEEP, we hardly leave the hospital for the next few days. For hours and hours we are out of contact with everyone but immediate family – David’s father and stepmother, my mother, my brother and his girlfriend, David’s sister and her boyfriend – who gather in the hallway outside. I was already on maternity leave when I went into labor, but David has to call his boss that first morning home, and his boss tells him to forget the world of work. How grateful we feel.

Only two people are allowed at the baby’s bedside at a time. We take turns bringing them in. Sometimes we let two people in together while we take a break. We break for the bathroom, for food down in the cafeteria. On the second afternoon, we actually leave the hospital for lunch while Silvan is off for a test. David thinks this is a good idea because the hospital food is so bland it’s hard to eat and because it will distract us while Silvan is in other people’s hands.

Going out is torture. All these people eating on their work breaks, choosing between rye and sourdough as if life itself hangs in the balance. Just choose and eat, you fools, I think, because back at the hospital real life is happening.

Holding Silvan

Holding Silvan